Legal Showdown between Homeless and Tulare County Sheriff

A large Tulare County homeless encampment is taking the sheriff's department to court to defend what they see as their home and a safe place to isolate amid the coronavirus pandemic.

On Jan. 18, Tulare County deputies served Tule River residents a "notice of trespass and clean-up." Deputies alerted the encampment residents that they would need to leave because neighbors and property owners had complained about conditions along the river.

Longtime residents of the river argue that the notices are illegal. Legally, law enforcement is obligated to notify homeless encampment residents when a clean up or eviction "sweep" is coming.

If deputies clean-up the encampment, the unhoused people fear they will have nowhere else to go. If they are forced to relocate to nearby Porterville, people at the river say they will be more vulnerable to the coronavirus.

"We like it here. We feel safe from the pandemic. If they move us into town, we'll be closer to the virus," said John Chavez, who has lived in a makeshift shack on the river for the past 18 months. "People blame the homeless for spreading COVID, but out here we're isolated. We wear masks. It's easy to social distance."

Michael Bracamontes, a civil rights attorney speaking at the river on Monday afternoon, said that it is illegal to remove people from public lands without a shelter available. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that doing so amounts to "cruel and unusual punishment," a violation of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

"There's clear legal precedent that without alternative housing, it's unlawful for law enforcement to harass, displace, arrest and threaten to prosecute people who are unhoused," he said. "And yet, here we are."

While deputies provided resources and housing information to people at the encampment, waiting lists for public housing in Tulare County consistently hover around a 1,000 families. It can take up to four years from the time an individual signs up for resources to moving in.

"We're the richest country in the history of the world, and we haven't met our responsibility to the poor, and especially here the rural poor of Porterville, up and down the Tule River," Bracamontes said.

The Tulare County Sheriff's Department said the Ninth Circuit ruling does not apply here because the river is not public land. Deputies, the sheriff insists, are upholding the law and preventing trespassing upon private property.

"We've received a lot of complaints about the plethora of homeless encampments set up on private property," said Ashley Ritchie-Schwarm, sheriff's spokeswoman. She likened the situation to an individual "setting up camp in your front yard."

"Whatever your feelings are about (the homeless situation), the law is the law," she said.

It will likely be up to a Tulare County judge to decide whether removing the residents — some of whom have lived in and along the river for more than a decade — is legal.

Bracamontes hopes the court will grant a restraining order to the encampment against the Tulare County Sheriff's Department, though a hearing is weeks away due to a backup of cases amid the pandemic, he said. The injunction would prevent deputies from carrying out the clean-up.

Ritchie-Schwarm said the department has not been served and could not respond to specific allegations as a result. She maintained, however, that the Tule River case would be cut-and dried.

"The law is clear regarding trespassing on private property. And these individuals are violating that law," she said.

Porterville City Councilman Daniel Penaloza supported the rights of those living on the river. He spoke at a Monday press conference announcing the lawsuit, saying that his city needs to do more to help its most vulnerable residents.

"I think that the Porterville City Council has not done enough, we have not done enough to address the solution," Penaloza said. "For me, this is a priority because I wake up to a roof over my head every morning. I wake up to be able to shower and have clean water.

"We all deserve that right, the human right to basic things in this life. And right now, this county has failed."

Community organizers hope to prevent an incident that befell another Tulare County homeless encampment at St. John's River in Visalia. During a January clean-up, a fire erupted in a large trash pile at the camp, consuming some of the people's belongings.

Authorities ruled the fire an accident. Visalia City Manager Randy Groom said the encampment was given more notice than legally required prior to the eviction, though some residents criticized the decision as "inhumane."

Groom countered that conditions at the camp had grown dangerous and become a liability. People at the camp, Groom says, damaged an irrigation levee and some of the endemic Valley Oak trees along the river.

Neighborhoods along the St. John's River Trail have also praised the city's action, saying that the trail has been cleaner and safer since the January eviction.

Meanwhile, others have said they notice more people walking around late at night and sleeping on sidewalks near shopping centers.

Some of the displaced St. John's residents have since ended up at the Tule River, according to Mari Perez-Ruiz, executive director of the Central Valley Empowerment Alliance.

Like St. John's, the Tule River crosses city and county borders, meaning the people who stay there exist in a kind of jurisdictional limbo, often bouncing from one side of the river to the other with little change.

Tulare County has the nation's highest percentage of chronically unsheltered people among similarly sized communities, according to a 2018 congressional report. The most recent census found 992 people experiencing homelessness in Tulare County, up 22% from 2019 and 60% from 2011.

The sobering statistic bears out at the Tule River camp, Perez-Ruiz said

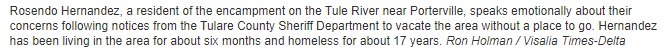

"If you talk to them, if you get to know them, you would know that they've been here for 15 years, five years, six months," she said. "But even if it was just a week, this is home. And there's nowhere else to go."

Joshua Yeager covers water, agriculture, parks and housing for the Visalia Times-Delta and Tulare Advance-Register newspapers. Follow him on Twitter @VTD_Joshy. Get alerts and keep up on all things Tulare County for as little as $1 a month. Subscribe today.